Painting Unicorns

The world is a confusing place. Life is complex, and things change so quickly that just as soon as we think we’ve got a handle on them, they shift and become something else.

One way of creating a measure of consistency for ourselves is using our minds to create concepts. A concept lets us categorise our experiences into groups of similar objects, people, places, and experiences and then figure out how these categories interact. In other words, a concept is a thought-thing we invent to make life easier to understand.

For example, a company is not a thing, it’s a concept. Most companies have a physical location, but companies also frequently change office or factory space. Many modern businesses have no specific location at all, with employees working remotely from literally all across the globe and moving around as they please. Similarly, factory or office workers are hired, fired, or quit; company owners sell their shares and someone new comes in take their place; even the products and services the company offers can change completely. And yet it’s still the same company.

So what makes a company a company is simply the fact that we all collectively refer to that specific system of human effort by the same name: Bob’s Auto Shop, or Walmart, or Spotify. This is exactly what makes a concept a concept. Although “Empathy” refers to physical processes in the world that really happen, the concept “Empathy” refers to a systemic phenomenon with no specific location, contents, and only a very general set of endocrinological and cognitive responses to the words, actions, and emotions of other human beings.

Where things get confusing is how we speak about empathy. Particularly in English, it is perfectly natural and normal for us to speak of a concept like “Empathy” in a way that suggests that it is actually a real physical object in the real phsical world, and not just an idea in our heads. But talking about an idea as if it were real doesn’t actually make it real, just as believing that something is true doesn’t actually make it true.

Reification

“Reification: Supposing, or acting as if one supposed, that an abstract quality has concrete actuality or existence; treating an abstract concept or construct as if it referred to a thing.1

You can’t paint a picture of a unicorn and then insist that unicorns really exist because you painted one. If you do believe that unicorns really exist, you are doing what is called reification.

You’re also reifying a concept if you believe that the company Amazon is a “person,” or that Anxiety is a “thing” in your head.

Let’s begin with a concrete example: money. Just about everyone believes that money is a real object in the world. But it’s not and never has been: A penny is money, but “money” is not a penny. A $20 bill is money, but “money” is not a $20 bill. Money is and has always been a symbolic marker of value, and nothing more. This means that literally anything can be used as money as long as we agree to treat it as such. This means, in turn, that I can trade and barter for the things I need without carrying a sack of apples around on my back.

Another way of saying this is that money is an abstraction, and as we proceed through history, we find that money becomes more and more abstract. Although there are examples of societies using sea-shells as money, initially it was objects that we still consider to be of material value: gold/silver nuggets or precious stones, then gold/silver coins and jewellery. After this came paper money and coins made of non-precious metals like copper, brass, and nickel. Governments then started making their bills out of plastic because it’s much more difficult for forgers to copy. And now the majority of financial transactions are done digitally, meaning that money no longer has any physical form at all. (This is partly why cryptocurrencies swing so much in value, they’re not tied to anything real, and so their value depends on the mood of the people trading it.)

What hasn’t changed about money is its abstract nature: the material it is made of has always been irrelevant to its value. Its value comes not from the fact that we can eat it or build things with it, but entirely from belief. Money works simply and only because we believe it does. We make money work because we need it to work, and because we make it work, it works; and so we believe it is real because it works because we need it to.

In our money-driven world, we have built the entirety of human society on a collective delusion. There is no physical money in any of our bank accounts, and yet we talk about those bank accounts as if they were a real sack of apples with a fixed, real, and finite number of apples in them. This is reification at its most refined.

Concepts are Not Real Objects

“Reification: …treating an abstract concept or construct as if it referred to a thing. The error is most insidious in psychology.”2

To bring this into the realm of psychology and psychotherapy, just about everything we talk about in these subjects are incorporeal reifications. Sadness isn’t a physical entity, any more than Happiness is, any more than Anxiety, Depression, or Psychosis are. Name literally any subject in literally any branch of psychology (with the possible exception of Psychophysics, pioneered by Gustav Fechner) and you will be talking about a concept, and therefore a reification.

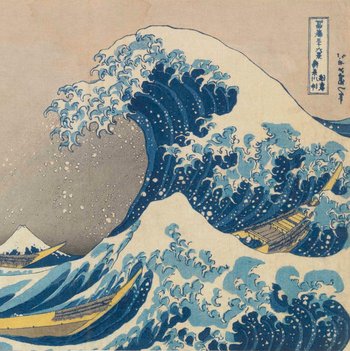

The central point isn’t to criticise psychology per se, but to accent the fact that concepts, ideas, thoughts, and emotions don’t exist as actual entities. A feeling is no more an object than a waves on the ocean is an object.

The Water is Wave-ing

A wave is not an object in the water, it is the water, and the water is wave-ing.

Similarly, a “thought” is a wave in the ocean of our mental processing. A thought is not an object in your mind, it is your mind, and your mind is think-ing.

To be more precise: The word “thought” you see on the screen is not a thing either, it is a visual symbol which refers to the spoken word “thought.” But, the spoken word “thought” also isn’t a thing. It is a sound made by air blowing over your vocal chords and articulated by the movements of your jaw, lips, and tongue. That sound is a verbal symbol which refers to the concept “thought,” but a concept also isn’t a thing. And the concept “thought” is itself only a symbolic reference to a complex wave-pattern between the billions of neurons in your brain.

And so, the word “thought” you see before you is a visual symbol which refers to a verbal symbol, which refers to a concept, which refers to an incorporeal energy relationship between billions of physical objects.

And so, a thought is not a thing, it is a “think,” and a think is a wave on the ocean of your mind as it is think-ing.

This is the nature of concepts in general and reification in particular: a reference to a reference to a reference to a relationship. None of it having any physical reality.

Anxiety is Not a Shoe

A picture of a shoe is not a shoe, but it refers to one. In the same way, the word-symbol “anxiety” refers to the emotional experience of autonomic fear-response at the thought of some future danger, but it isn’t itself that experience. So the problem here is that anxiety is not like a shoe.3 Take one of your shoes off and hold it in your hand. Then try and take your anxiety out of your brain and hold it in your hand.

A description of “anxiety” symptoms is not only not anxiety, but it doesn’t even refer to anxiety itself, because anxiety isn’t a thing. Anxiety is a multi-dimentional interaction pattern between a number of different brain regions and organs of the endocrinological system in your body. That pattern comes and goes, but the organs don’t. Anxiety comes and goes, but the brain doesn’t.

So when we say:

I have anxiety.

We actually mean:

I am experiencing fear and worry about a future event that I feel I cannot control and which I am frightened will not work out the way I want it to.

If anxiety is your jam, you will probably be very worried about a lot of things, and you will probably worry a lot more than you need to about things that you don’t need to worry about, but that doesn’t mean you have a thing in your brain called “anxiety.”

Fear is not a “psychological object,” it is the person’s subjective experience of the total state of their body as it reacts to a person, animal, or experience which threatens to harm that body.

Fear comes and goes. The body does not.

A Useful Ability

Our emotions are ephemeral, transitory, and difficult to nail down. So we use our mental abilities to make real-seeming “concept-things” out of intangible and transitory states of metabolic and cognitive arousal. This gives us something concrete to hold onto when talking to others about what we are experiencing.

This is incredibly useful and the power of abstract and conceptual thought is one of the primary abilities that sets human beings apart from our closest chimpanzee and bonobo cousins. All of science, engineering, medicine, computers, and literature are literally impossible without this ability and they are indispensable to the effort of making life better for ourselves.

Exactly like money, however, our reified concept-things quickly become real-because-we-believe-they-are-real, and this is where things start to go a bit sideways.

A Problematic Ability

Most of us feel a powerful longing to “have” more “happiness,” and struggle to understand why we never seem able to “get” more of it. We long to “get rid of” sadness, as if it were asbestos in an old building. But when we try, we find that not only is there no asbestos, there is no building. Happiness and sadness simply don’t work that way. Nor do depression, anxiety, mania, intrusive thoughts, or frustratingly-resilient-attachment-feelings-towards-an-abusive-romantic-partner-who-I-really-want-to-break-up-with.

The main problem with how we talk about emotions is the same one we have with money. Reification. We talk about emotions as if they were objects, which convinces us that they actually are objects, and so we expect them to behave like objects. But because they aren’t objects, they literally can’t behave how we want them to, and we get very confused and upset when they don’t.

Thus the great tragic irony of life: You can’t find happiness because it doesn’t exist. Worse yet, the harder you try to find happiness, the unhappier you become.

This highlights the central problem that reification poses for psychotherapy, psychiatry, self-help, and psychology in general. The believe that emotions should behave like objects is so deep that most of the first year of sessions is taken up by simply learning how to experience your emotions for what they really are instead of what you wish they were.

It takes a surprising amount of introspection and emotional effort to realise that your emotions are not objects, but transient states of feeling and thought; the body’s signals to itself about how it is doing at any given moment and what it needs to continue surviving.

The sad part is that we are taught to think and speak this way about emotions, even though it is fundamentally incorrect. There is no grand conspiracy here, it’s simply that thinking of concepts as objects makes the thinking easier. The false understanding is an unfortunate side-effect that few people notice, and even fewer manage to correct. For me, personally, this is a bit of an ambivalent point, if people were taught a less incorrect and misleading view of self and emotions, I would pretty much be out of a job!

Unicorn Paintings

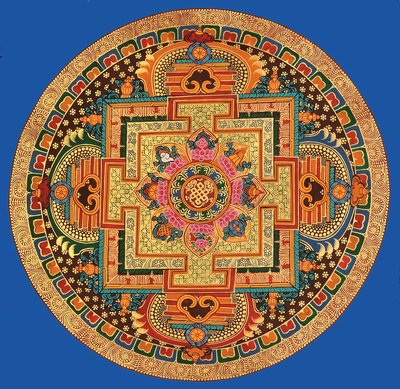

You can’t draw a unicorn and then claim that because you drew it, unicorns must therefore exist in real life. Most of modern psychiatry, however, is based on psychological unicorn-paintings, ie. pre-conceived categories of experience (aka. diagnoses and mental diseases) for which it then cherry-picks evidence to prove that the unicorn is real when it actually isn’t.

The DSM in particular, on which all psychiatric diagnoses are based, is 1000 pages of unicorn paintings. Even its advocates acknowledge that its categories are largely arbitrary and should never be applied without reference to the concrete facts of a person’s real life and real expereinces.

Consensus Reality

These days, however, what almost always happens before people go to a psychotherapist or a psychiatrist is they look their weird/bad feeling up on the internet, and they almost invariably find a set of DSM diagnostic criteria, which they they apply to themselves. Thus they discover that they have a “thing” called “Insecure Attachment” (or whatever). The more they read about it, the more they become convinced that they do in fact have this thing:

“Because, look, I have so many of the symptoms.”

Unfortunately, any one of the “specific symptoms” I might look up is also associated with a bunch of other so-called disorders. And suddenly I discover that not only do I have Insecure Attachement, but I also “have” bi-polar, schizophrenia, ADHD, early-stage heart disease, and a terrifying and incurable form of brain cancer.

Then I go to the doctor and the doctor confirms that I have the thing called “Major Depressive Disorder” (or whatever), and then prescribes a medication that will get rid of the thing.

The problem here is not that we’ve developed concepts to describe complex phenomena. The problem is not that many psychiatrists and therapists don’t understand the DSM or how to apply it correctly. The problem isn’t even that we’ve all been convinced into holding delusional beliefs that inaccurately represent reality.

The problem is that this reification-based way of understanding the world causes me to misunderstand myself and the nature of the problem I am struggling with. This leads me to make decisions and take actions that often actively make things worse.

The problem is not that the idea is wrong, it’s that the wrong idea makes me hurt myself.

It’s Not Just Psychiatrists

Psychiatry takes a lot of flak for pathologising perfectly normal human expereinces with its spurious diagnostic criteria, all while functioning as a drug-pusher for pharmaceutical companies. Rightly so. There are lots of psychiatrists who do exactly this. But not all of them. And to be fair, there are many, many psychotherapists and counselors who get just as bamboozled by their own favourite concepts and theories.

As stated above, almost the entirety of Psychology is quagmire of “it’s real because we believe it’s real” reifications and science-magic hand-waving.

This is partly why there are 200+ psychotherapy approaches, most of which are functionally identical. The different names and therapy procedures emphasise the different theorietical orientations (ie. the preferred concepts/reifications) of the people who practice them. But if I’m completely honest, as far as I’m concerned, it’s all marketing for the personal brand of the theorist who came up with the idea and needs to sell some books.

So, since I am a therapist, and therefore am as guilty of reification as everyone else, let’s look at an idea that I like and sometimes use in my practice.

True Self / False Self

This is the idea that within everyone there is a “true” self and a “false” self. Where the True self comprises all of your honest thoughts, feelings, and desires, the False self consists of all of the things you do, think, and feel because you are socially obligated to do, think, and feel them.

Doing and saying things that don’t align with your values and desires is often profoundly uncomfortable, but most people do it for so long that it simply becomes normal. Eventually, they start to believe that the “false” self is who they actually are.

Most people float along in this state until they have some disruptive or revelatory experience (a car crash, a bad breakup, a mushroom trip, or the death of a loved-one) and they’ll suddenly realise that they’ve been so taken over by the “false self” that they no longer even know who their “true self” is.

They then come into therapy to discover their inner True self and learn how to drop the False self that has been controlling them all of their lives.

I actually quite like this idea, because it makes it much easier to talk about nebulous themes like identity, will/desire, compliance/conformity, and so on. But if you pay close attention to your own thinking and feeling as you talk and think about the False Self idea, you can feel yourself becoming ever more convinced that there really is a real other “false” you inside your head that is controlling your actions.

There Is No Devil, There’s Only God When He’s Drunk

The False-Self concept is very useful one, but… there is no devil, there’s only god when he’s drunk.

There is no false self, any more than there is a true one. Any more than a wave is an object inside of an ocean. A wave is the ocean waving, and my “false” self is me behaving incongruently.

The False self is me, and the True self is also me, and unless I am experienceing an exquisitely rare case of genuine split-personality, any difference I perceive between my “selves” is the result of the inner dissonance of behaving incongruently exacerbated by me reifying a “false” version of myself and experiencing that “object” as if it really existed.

As much as I like the idea, I have to admit that factually speaking, it’s junk. But as with most of how we talk about emotions, the real problem with the False-Self idea is not simply that it’s factually incorrect.

The problem is that it lets me excuse my incongruent/dishonest behaviour by leveraging a widely-held and theoretically sound belief so that I can dodge responsibility for my actions: If there is a false self, and if that false self is really real, then it wasn’t actually me who did or said that hurtful thing. It wasn’t me, it was my “false” self.

Good Old Denial

The False Self construct, and reification more generally, often functions in this way. Specifically, it works in service of denial and the many other defence mechanisms that rely on it.

I don’t want it to be true that I did something hurtful, and so I find a way of making it someone else who did it, even if that someone else was also me.

The hard part is that once you become convinced that there is a true and false self within you, it really does feel like they really are two different selves in there. This is partly because behaving incongruently is inherently alienating, but it’s mostly because I have come to believe in the divide between two “parts” of myself and orient my perceptions to fit the spurious model.

As I said, conceptualising the True/False self experience is extremely useful, because it allows you to acknowledge for the first time that how you are now is different from how you want to be. The rationalisation and denial defenses play their positive parts too: they protect you from the guilt and shame of having deceived yourself for so many years and allow you to start making the changes you need to make without (too much) embarrassment. But eventually I have to admit to myself that by leaning on this concept, I’m still deceiving myself.

Through the Looking Glass

You can’t paint a picture of a unicorn and then insist that unicorns exist because you painted one.

This, ultimately, is the main problem with reification: it’s very convincing and a very convenient way of re-shaping reality in a way that suits us. We all have an innate desire to understand the world, and the concept-objects we create give us simple and satisfying answers that allow us to stop worrying and get on with the actually important part, living.

This is partly why people so often turn nasty when you challenge their fundamental beliefs. Most of those ideas are reified concepts (eg. capitalism, the holy trinity, Che Geuvarra, blood purity) and by challenging them, you are threatening to remove the foundations of that person’s entire understanding of the world. If they lose that, they fear they’ll lose their ability to function, and therefore their ability to survive. In a sense, taking away someone’s core beliefs is tantamount to killing them, and it certainly feels that way. And so they protect themselves, sometimes literally with violence.

Another Turn of the Wheel

The exposition and criticism of reification has a long history that extends back across thousands of years. After all, the whole goal of emotional, intellectual, and spiritual development (whether through psychotherapy, psychedelics, or spiritualism) is to learn to see through the veil of real-but-imaginary beliefs to the actual reality hiding behind. And in my opinion, the single most important understanding in all of this is how completely we are deceived by our various reified ideas and beliefs.

So, I’m really not saying anything new here. Most of the world’s religious and spiritual traditions warn against reification both explicitly and implicitly.

Thou shalt make no graven images and worship no false idols.

If upon the road of life you meet the Buddha, kill him.

In psychology-land, critics of psychiatry have been saying all of this same stuff about diagnostic categories since psychiatry was invented and there are many good and convincing arguments for why we should abandon the DSM and ICD “mental disease” classification systems. Most of these boil down to; because they do more harm than good.

If you’re interested, there there are already a number of very strong alternative systems which do a much better job of actually helping people who are suffering emotionally.

A Tool to be Used

At the same time that all of this is true, reification is also one of our most powerful mental tools. Ultimately, it results from our desire to simplify the world enough for our little and limited human brains to comprehend at least some small part of the inconceivably vast and complex reality we inhabit. This is a very useful ability, but it is also one that can easily run away with us.

Even once you get a handle on the concept and can consistently spot yourself doing it, it still takes a lot of effort to remind yourself that just because it feels true, that doesn’t mean it is actually true. Which is basically the heart of the dilemma of being human.

So the final point is that creating, using, and reifying concepts doesn’t have to be problematic, as long as we remember that a concept is a thought, and a thought is a think, and a think is a wave on an ocean that never stops waving.

A Comprehensive Dictionary of Psychological and Psychoanalytical Terms, Horace and Ava English↩︎

A Comprehensive Dictionary of Psychological and Psychoanalytical Terms, Horace and Ava English↩︎

There actually is a metaphysical sense in which anxiety is exactly like a shoe, but that would require a very long discussion about quantum physics and the nature of reality that somewhat outstrips the space available here.↩︎